The Gold Coast of Africa Part II: Becoming Humanitarian

Ghana is Africa for beginners. Though the country’s name roughly translates to Warrior King, they successfully incorporated tribal leadership into their democratic institutions. The Ghanaian government invested in education, infrastructure, world markets, and embraced globalization shortly after becoming the first African country to win independence from Britain. This helped bring stability to the nation, making it safer for travel, business, and humanitarian investment.

“Ryan, wake up!”

I heard Phyllis’s heavy accent outside my dormitory. It was still dark out, and I was confused whether I was tired from the jet-lag or unexpected wake-up call. I quickly packed my day bag. Everyone except my mother and I were waiting at the van.

We rode a few hours to the first village our team would work in, catching bits of sleep on the slow drive. We arrived in the AM, quickly setting up a data collection point and scales. I was surprised by all the beautiful colors the rural Ghanaians wore. One by one, we took measurements and information from children and mothers who requested aid through the program. Some of the kids had never seen a white person before. All eyes were on my mother and me. Most of the children were curious about who I was, where I came from, and what I was doing. A few were afraid to the point of tears, yet some sought to practice their English with me. I was delighted and flattered to do so.

While working, an adorable little girl with the most infectious smile followed us around. She spoke no English, but Phyllis told us she wanted to hang out with the team for the day. I don’t know if Phyllis knew her parents or not, but she did accompany us and was absolutely delightful. I could be wrong, but it seemed like the culture in Ghana was very community-oriented, and if this kid wanted to spend time with Westerners, who were few and far between in her neck of the woods, Phyllis wouldn’t deny her the experience.

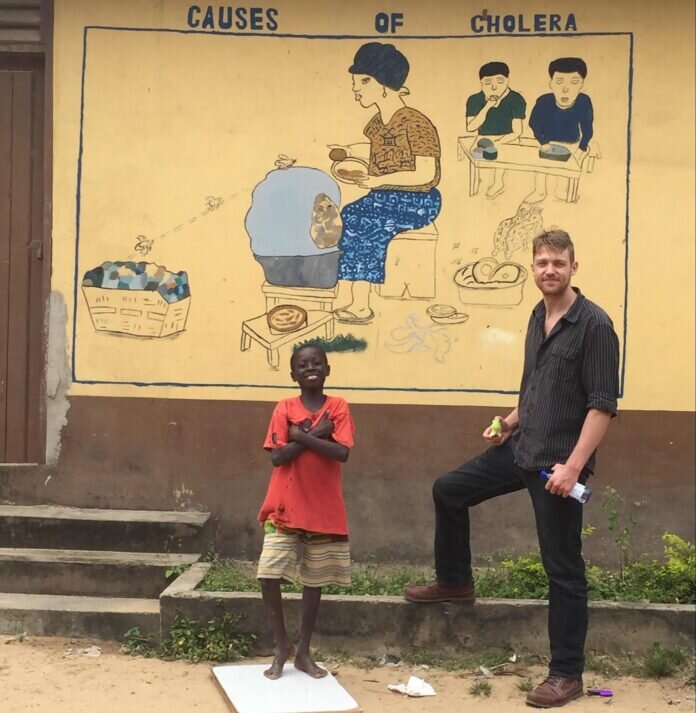

We visited many villages in the following days, taking measurements, data, and delivering aid. Each of the villages had their own charm. Some were more developed than others, but each had a community center. One village in particular was very dry and seemed to have little water available. This village also had an outbreak of ringworm, which I myself had contracted in a filthy South Korean army barracks years earlier on a field training exercise with Special Forces. I couldn’t shake the compulsion to wash my hands whenever I could break away from the group. Despite the ringworm, malnutrition, and other health ailments, the children smiled in the most pure and unbroken way I’d seen in all my travels. I used to think it was cheesy and classless when Westerners would travel to impoverished regions of the world and take pictures smiling with the local starving children, but I was starting to understand. These kids had little in the way of comfort and nutrition we’re so accustomed to in the West. Most of the parents I met were snappy and mean with their kids, but their children endured and always smiled so beautifully. There was something special about it.

Early on during the adventure, someone made a joke about my mother getting a weave. Somehow this turned into a serious consideration. Seeing as some of the children had never seen white people, we began to think it could help her build rapport with the locals. She pulled the trigger on it without hesitation.

When we walked out of the market on the outskirts of town to meet our driver, I saw an animal calmly walking toward us on the sidewalk. At first I thought it was a donkey, albeit with thick front legs. It got a little closer and realized it may actually be a big dog. When my vision sharpened, I could finally see that the creature ahead of us was actually a huge baboon! Unlike the cute and sassy baboon on Disney’s Lion King, this animal knew he was boss and owned that sidewalk, strutting with confidence like a Drill Sergeant in a hall full of Privates. Phyllis had us move out of the way, but not as far as I was comfortable with. She insisted it was fine. This was the first of many baboons I’d see on the trip. The locals lived among them without problems, but I was certainly out of my element casually strolling past packs of creatures that could tear my head off!

One day, we drove to a village in the northern mountains. The air was surprisingly cool, which I welcomed after spending my first few days under a sweltering jungle sun. Green vistas of rolling grass and forested hills were dotted with low-hanging clouds. We were in a routine at this point, taking measurements, data, and notes with machine-like efficiency. At this hilltop village, there were a small handful of children with cleft lips and palates, usually caused by the mother’s lack of folic acid during pregnancy. This is easily preventable with prenatal vitamins. We noted this in hopes the foundation would make prenatal vitamins a priority for the region. I took a small break from collecting measurements to appreciate the view, and down the hill saw two well-dressed white men walking up. I was curious until they got closer, when their white shirts, ties, and name tags gave it away. Mormons! The two Mormon missionaries struck up a conversation with me, saying it was good to hear my accent. One of the missionaries grew up an hour’s drive away from my home town, and there we were conversing on a remote Ghanian hilltop village. Small world.

After regrouping and resting back in Kpong, we drove toward the seaside city of Cape Coast. The crisp, salty air pleasantly permeated the town and outlying villages. We had a rewarding dinner of sausages, curried fries, and banku at an outdoor seaside cafe, birds coying overhead as they rode the thermals and scavenged for our scraps. After dinner, we strolled down the beach. My mother, barefoot, started worrying me when I got close enough to the shore to see it was trashed. Needles in the sand are quite an attitude changer.

Later, we found out about a music festival in Cape Coast. The team had a great time. I met some cute Ghanaian, Israeli, and German girls at the chaotically cheery venue and danced the night away. A stocky, charismatic Ghanaian man wearing a red polo shirt and cutoff Levis struck up a conversation with me, then I realized he was flirting. I told him I didn’t swing that way and he danced his way back into the thick, lively crowd. Less than twenty minutes later, I was dancing with a tall, lean Ghanaian woman who had an unforgettable smile, when I noticed the man in the red shirt dancing with my mother! Apparently he had a thing for abrofo, “white foreigners.”

After nursing a hangover the next morning, we drove into the sticks so far that we had to ferry our van across a river, clearing military checkpoints on both sides. We worked in a village that had been a British colonial plantation, the skeleton of it’s old cathedral peaking above the jungle’s dense canopy. This far into the jungle, I noticed more women had facial scarification markings, indicating the tribe they belong to. During screenings, we heard shouting and various clanking noises in the distance. They were getting closer. Then we saw hundreds of smiling, dancing villagers of all ages racing down the main unpaved road in celebration. We asked Phyllis what was going on, and she told us someone had won an election.

In another celebratory display at a different village, we stopped in the middle of a crowded road as hundreds of people flowed through the streets for a funeral procession. It was the least somber ceremony I’ve seen. Participants danced down the street in colorful suits and dresses, tossing the chromed coffin up and down as the people cheered. What would be incredibly irreverent in most of America was a beautiful celebration of life across the pond at the equator.

We spent a few days in this area and made our way back to Cape Coast, where we stayed at the Hans Botel. The “Botel,” situated on a riverbank, was an old German waterpark at one point. It had since changed hands a few times, and someone decided to neglect the swimming pools. Crocodiles moved in, so they made it a tourist attraction with reptilian tours and feedings. It was fun to sit at the bar, throw a french fry at the water, and see crocodiles scramble to the surface for it.

I was consistently exhausted from the constant travel, unfamiliar food, and hard work, but was having the time of my life. I was proud of what we were accomplishing. I sincerely felt like I was impacting people’s lives. Weeks before I had no idea I’d be roaming that lively little corner of the African continent. The trip was coming to an end, but I still had a big lesson to learn in the halls of an old European seaside castle which harbored hundreds of thousands of slaves and clergymen. One of my biggest takeaways from West Africa brought to reality the Holocaustial horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, and our ongoing ignorance of it.

To be finished in part three……

Written By Ryan Sefid

3/30/20